As the capabilities and companies in the solar market have now grown far beyond the low-hanging opportunities, we find ourselves pouncing on sound but short-lived requests for proposals. Hundreds of companies bid in to these processes, and the market is split between bidding to win and bidding a financially sound price. Companies often cannot do both.

Wouldn’t it be nice if there were one large market with enough opportunities for everyone, with superb solar resources, supportive regulations and comfortable energy prices that aren’t driven by incentives?

Such a market exists right next door in Mexico, where wind energy projects have enjoyed such a climate for several years. Now it is solar’s turn. Mexico – ranked 14th in world gross domestic product – not only has energy “prices to beat” set high by the country’s sole electricity provider, Comisión Federal de Electricidad (CFE), but historically, the energy prices have escalated at rates up to 8%-10% per year. Coupled with the cost decrease that solar systems have gone through in recent years, solar has reached grid parity in Mexico. This is even more profound when considering that Mexico does not offer any direct subsidy to solar, other than an accelerated depreciation schedule.

Grid parity opportunity

While some countries are working to create legislation to jump-start their energy sectors, virtual net metering and virtual energy storage laws are already on the books in Mexico. By contrast, one of the U.S.’ most advanced renewable markets, California, has yet to implement comprehensive virtual net metering, although its Green Tariff Shared Renewables Program (SB 43) is coming close.

In Mexico, solar developers are not selling “green,” as they have needed to do in markets of the past; instead, they are selling a better-priced product, and customers are buying because it benefits their bottom line.

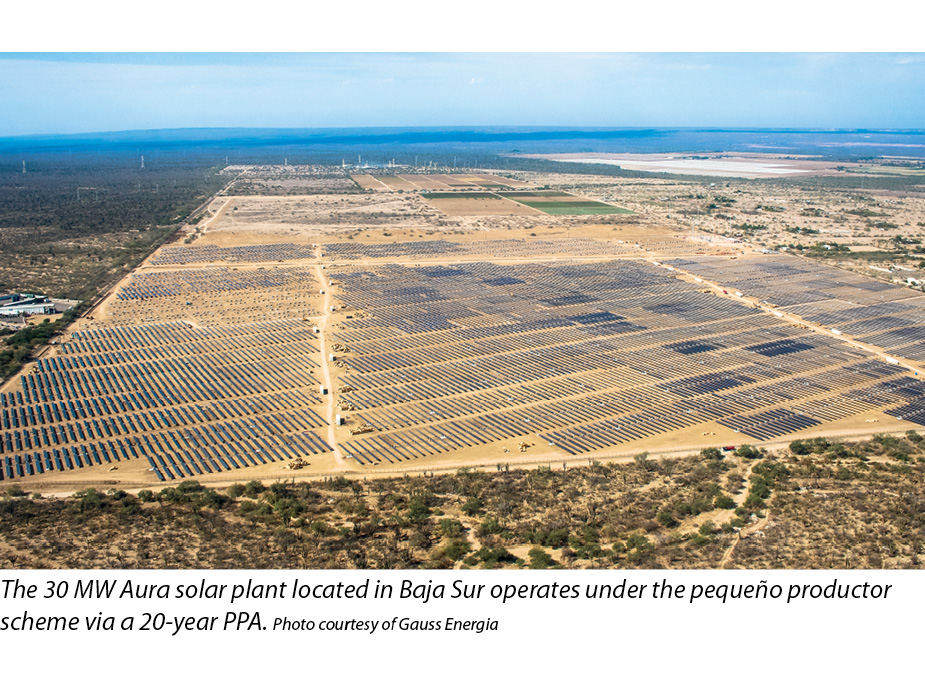

While large wind projects, such as the 250 MW Eurus project in Juchitan, Oaxaca, have been developed under this scheme as far back as 2009, the drastic decrease in the cost of solar power systems over the past few years has created an opportunity in Mexico. As such, a huge boom in power from solar generating facilities is predicted this year. Among other indicators, the world’s first spot market solar energy project was completed in the state of Baja Sur this past year – a 30 MW facility developed and constructed in less than 12 months.

Currently, there are essentially three ways to sell energy under a power purchase agreement (PPA)-type structure in Mexico. One is to supply energy to CFE under a spot market-type contract as a small-scale independent power producer (IPP), or small producer (pequeño productor). Developers and financiers thoroughly review the local historical nodal price of energy to see if they can finance and make a sufficient return on their projects. While this is an interesting scheme, the boom is happening in the self-supply (autoabastecimiento) and cogeneration (cogeneración) schemes.

These mechanisms offer a potential energy buyer two options.

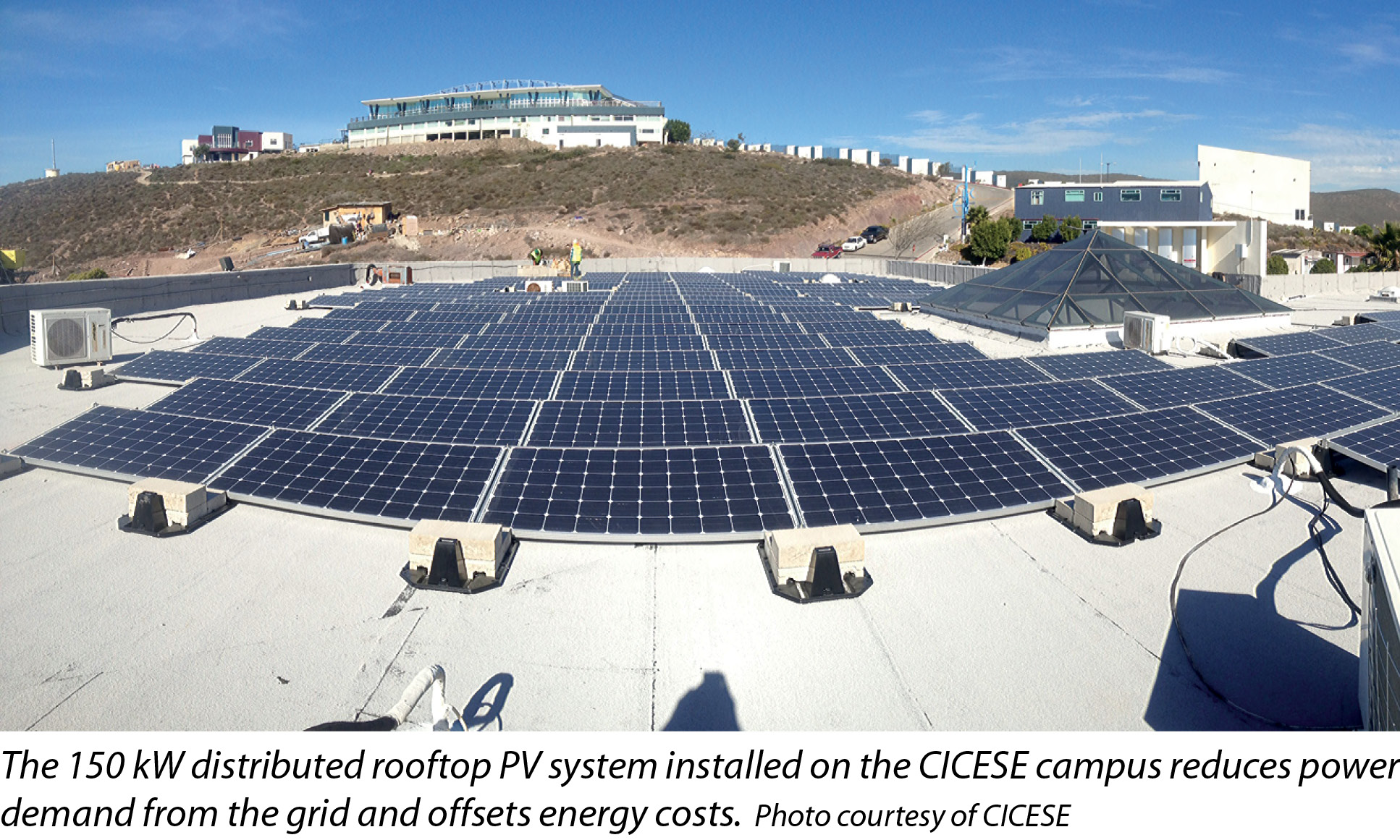

Cogeneration. Under the cogeneration scheme, the buyer can offset the energy usage and demand charges with a project connected behind the meter. This is not unlike net-energy metering regulations currently in place in the U.S. (e.g., a large retail store with a large rooftop can install a solar system and offset its energy usage and demand).

Although the system may not be owned by the retail store, it is installed on the buyer’s property, and for regulatory and metering purposes, this electricity is produced for self-consumption. Individual rooftop systems are limited in size by the space and structural conditions of the building, and from a financial perspective, these types of projects are often developed as a portfolio of systems such that the combined volume generates the expected returns. PPAs under this scheme look to the buyers’ creditworthiness for financeability.

Self-supply. Under the self-supply mechanism, the buyer or a consortium of buyers can purchase energy from a project not on-site. The buyer offsets energy usage, but not demand-related charges. This scheme provides some of the greatest savings given by the economies of scale of large power plants located in the best resource locations.

Under the self-supply scheme, buyers will take advantage of energy generated and wheeled to them from a seller’s facility that may be located far away. The energy wheeling costs have been historically so low that, colloquially, they have the nickname of “postage stamp” (estampilla). These rates are currently under revision, and while only modest increases are predicted, this issue has slowed down some projects in development in Mexico.

The buyer(s) and the seller create a joint venture such that from the regulatory and metering perspective, the electricity produced remotely is used for self-consumption. The country’s virtual energy storage regulations allow the customer to make use of the generated power at any time – day or night – with minimal added cost. PPAs under this scheme look at the consortium members for their creditworthiness analysis.

¡Bienvenidos a México!

Each of these schemes has its own benefits, costs and legal hurdles, but underpinning all these opportunities is the market-clearing price for energy, set by CFE’s energy prices and historic annual escalation trends.

The government of Mexico recently passed landmark legislation around energy reform, which will have a major impact on increased production of petroleum and gas resources. These reforms will also change the electricity sector, and it is projected that the legal and regulatory challenges for private off-takers and producers of solar electricity will be reduced. For instance, there may not be the need to create joint venture arrangements between off-taker and producer, or other similar mechanisms to assure self-consumption.

Dino Barajas, a partner with the law firm Akin Gump and a 20-year Mexican energy market veteran, notes that the Mexican energy market has provided developers and investors with a stable and profitable investment environment since the introduction in 1992 of private investment in the power sector. Barajas says the defining factor separating successful developers and investors from the rest of the market has been appreciating the potential pitfalls inherent in the market and addressing them head-on during the initial development phase of a project. Incorporating the lessons learned in the past 20 years will lead to increased rates of return and shorter financing cycles for prospective projects, he concludes.

Mexico’s governing energy body, the Secretaría de Energía (SENER), sees a bright future for renewables and self-supply in the country. The country plans to continue generating a major percentage of the country’s energy through CFE, but SENER forecasts that the small IPP and self-supply scheme will take on a prominent role in increased renewable energy production in the near future.

The chart shows a few of the important price points for energy in Mexico that a developer would need to beat – in addition to other developers’ pitching prices – in order to strike a deal.

“There is a lot of hesitation in investing in renewable energy systems ‘on your roof’ here,” says Rodger Evans, chief researcher of the federal Alternative, Renewable, and Sustainable Energy Laboratory (LEARS) in Ensenada, Baja California, speaking about the self-supply scheme. “Allowing several businesses to be part of a buy-in has the appearance of being more secure: It is not on your roof, and you don’t have to maintain it. This is the real beauty for a business owner with these systems. The bureaucratic and technical issues are taken care of by your buy-in partner, and there is no need to change any of the installations on your business.”

Interestingly, to date, the energy buyers have been more involved in the development process than in other markets, given the legal structural requirements of the self-supply scheme. In the process, energy off-takers are learning the business and often are bankrolling or investing in their own projects. Until legislation changes are defined and approved, international firms seeking to develop in Mexico need to recognize this and treat off-takers as partners – and not just customers – in the process.

Many market forecasters and industry veterans see the potential in Mexico – some so much so that they have moved to Mexico. For instance, Alfonso Tovar, formerly with Black & Veatch, moved to Mexico City last year and started his own firm, Solaris PV.

“I knew this market had a lot of potential, but I didn’t know when it would pop,” Tovar says.

The market is currently “popping,” and he notes that while solar in Mexico represents a big opportunity, it is still an emerging market with pains and aches all over. Nevertheless, Tovar says it is one that is certainly learning and growing.

Developers will need to adapt to the specific local issues and business culture if they wish to be successful. And that does not just mean being able to speak Spanish.

SENER says Mexico should have 6 GW of solar installed by 2020. At present, less than 1% of that is installed. When solar boomed onto the center stage in Spain, Germany and some other early adopters, it made quite an entrance, with many more megawatts installed than expected. However, those were “artificial” feed-in tariff (FIT) markets. By contrast, Mexico is perhaps the world’s first unsubsidized “real” solar market of size.

We are seeing development issues described in this article come into play, but we are also starting to see large operating and construction-ready projects. The natural growth of this real market may surpass expectations in the near term, but without any subsidies or FITs to roll back, Mexico’s solar market is almost certain to persist in the long term.